|

The darker nights of autumn were advancing rapidly at the beginning of September in 1939, but it wasn't going to be the usual progress of nature that would make this winter the darkest and gloomiest for many a year. And it wouldn't be for just one winter but six. Six long, cold winters which our post-war children would hardly be able to understand and even more so the children of the last two or three decades.

In my most formative years, between seven and nearly fourteen, I lived through some of the most momentous years in our history but for a child of nearly seven my own little world was more black and white with very little depth and the climactic events slipped over my head and disappeared in the ether.However,visual and more concrete events were happening around me and these became vivid memories that have not dissipated over the decades since the end of the world conflict.

At the latter end of 1939 my head seemed to be bombarded by names and words that were forever being repeated; Churchill,Chamberlain,Hitler,blackouts,air-raids,rationing, were some of the many that the adults were throwing about like confetti at a wedding. These words impressed themselves on my mind and very soon I began to understand their meanings.

The black-out and air raid sirens stand out in those early months of the war.Suddenly the Gas-Lighter didn't attend to his duties of lighting the gas mantles of the street lamps,which at first was of no great inconvenience but as the months advanced,with moonless and cloudy nights the situation became oppressive;and the gloom became more so as each householder was ordered to install blinds or heavy materials through which the light couldn't penetrate the blackness outside.If a person carelessly left the light on without the curtain being drawn properly, you would soon hear the shout of the air-raid warden , "Put those lights out".

Inside our house and everyone else's, blinds were being fixed and even in some cases window panes were being painted black,usually these were the smaller transom windows which lowered the cost of curtains and blinds and stopped any chink of light from escaping.Also on the windows people were placing strips of adhesive brown paper in criss-cross fashion to lessen the danger of shattering class in case of a bomb explosion.

Soon we heard the wail of the cathedral siren, no doubt at first to test the efficiency of the siren and also to make the public aware of the sound and the action to be taken.We all learned very quickly of a 'warning' and a 'clear' sound of the sirens. We needn't have worried too much about the cathedral siren because at each air raid the pit buzzers would sound all around the city and in those days we were surrounded by pits.

Very soon we became acclimatised to the air-raid warnings. Also early in the war we were all given an air-raid shelter; some for outside of corrugated sheets, called 'Anderson' shelters, and indoor ones which resembled iron tables,the top being a steel sheet and the sides of steel mesh. I could never understand why most families received the 'Anderson' type and a few families received the inside'tables'. In Ashington in Northumberland it seems that all families received the'table'type but they also had the added security of purposely built outside shelters for communal use. At first as soon as the warning sounded there was a swift exodus from the house to the shelter with bedding and clothes to keep warm.We soon learned that the shelters were not nice places to be in. If the weather was good and warm then it was reasonably comfortable, but on wet,windy and cold nights it was very unpleasant and damp and cold. Some people seemed to make them very liveable by laying a concrete floor to keep some of the dampness out but it never really worked with the cold,snowy wintry nights.And the worst time was when you were lovely and snug in bed and the siren sounded, then you were lifted or scrambled into the shelter shivering and half asleep and we huddled together awaiting the 'all-clear' to sound.

Every Family was affected by the war,albeit some more so than others. We were all inconvenienced by the blackouts,sirens,rationing and many other rules and regulations which were created by the Government as emergency contingencies for our own benefit. But the most traumatic for nearly every family was the loss of loved ones called up for the crisis in one of the three major

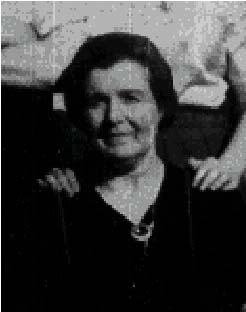

services: the Army,Navy or the Royal Air Force. Families were disintegrating all around us; Fathers,sons,brothers and sometimes even daughters. My own family was certainly called on to do its share. Even as a toddler I could feel the tension in the home;my Mother was a born worrier but the atmosphere was something different from the normal domestic incidents. The three eldest sons in the family would all be eligible for service during the early years of the war and she was too well aware of the situation which constantly gnawed at her heart; and all of us could feel the tension,in fact you could almost cut it with a knife. Soon her nightmares would become reality.

I was hardly old enough at the time to get caught up in the euphoria of the youths in our neighbourhood. At the beginning of the first World War young men enlisted in their thousands to become part of the exiting events ahead and it seemed that they were not going to be any different this time. My Father wasn't a man for making profound statements but after being involved in trench fighting in The Somme and other battlefields of the first conflict he felt he had to say something when he saw his sons and other youths becoming intoxicated with the thought of fighting the Germans. The family always remembers the words because they were told hundreds of times forever afterwards by my Mother and my elder brothers: "The silly buggers," he said, " They don't know what they're letting themselves in for!".

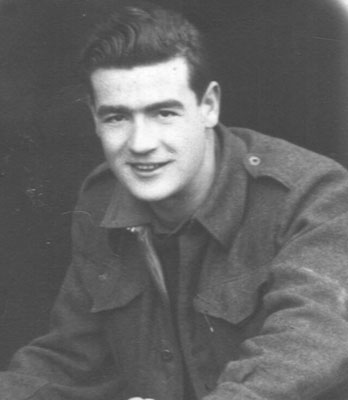

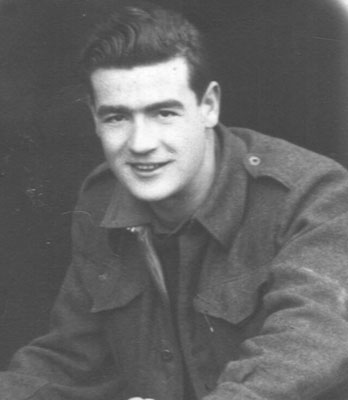

My oldest brother soon found out. He was the first to 'join-up'.He couldn't wait to be conscripted as very shortly, thousands of others would be. Gavin enlisted and underwent a medical at the Elvet Methodist Church. He was soon accepted and amid floods of my

Mother's tears he made his incredible first journey in the army all the way to Gateshead. There he underwent training in the D.L.I. at a school in Askew Road sleeping on makeshift mattress's stuffed with straw which was a do-it-yourself job as his first duty in the army: they were given palliases and instructed to fill them from a pile of straw close by. His training was only to last months before he was given embarkation leave prior to joining the rest of the B.E.F. heading for Dunkirk. Gavin found himself transferred to the Black Watch (Tyneside Scottish), and it was in this uniform that he had a photograph taken which was my Mother's favourite momento for the long years ahead.

After the traumatic news of the defeat in France and our army heading home by any means whatsoever my parents were grief stricken. Nothing was heard from Gavin; no letters, no official information; it was as if the system had broken down. My Mother was distraught and latched on to any rumour that was offered. She received two pieces of information (rumours) that some friend of his had seen him somewhere. Once he was seen riding on a tank and safe and well. But as with all rumours there was no foundation. She searched the city for the two boys who had made it home to ask where they had seen Gavin but each one she found and questioned had no idea what she was taking about and certainly hadn't seen Gavin! I remember vividly going to school at the time and seeing soldiers wandering through the town in dishevelled states with unkempt bits of uniform mixed with civvy jackets or trousers and all in need of a shave. It all seemed so strange because all the soldiers I had seen up until then were very smart and clean, a deep contrast to the forlorn and bedraggled remnants after Dunkirk.

The following weeks were very distressing for the family. I believe my parents received the usual telegram that Gavin was missing. During this time Gavin was in captivity as a prisoner-of-war and marching across France, Belgium and onto Poland where he would remain for the next five years. Eventually we did receive official word that Gavin was a prisoner which in a perverse way was a relief to my parents. Still nothing was straight forward. My Mother sent letters which Gavin never received and food parcels which usually where returned with the contents battered and unusable. When contact eventually came his letters and cards where mostly too heavily censored to make any sense. I remember being mesmerised by the German lettering around the edges of the mail he sent and the heavy scores across most of his handwriting that obliterated most of his words. He later told me that his own letters were much worse (if this was possible), sometimes all that was left was my Mother's Love and name at the end of it. Censorship later relaxed to a certain degree but still plenty of those thick, black crossed out lines that became the hallmark of my parents mail.

Still, he was alive, for which we could thank God. But many where killed or seriously wounded. One family I knew (wife and three children) never heard of their Father again only the fatal telegram"Missing, believed killed in action",but they never knew how, where or when it happened.

My second eldest brother, Peter, applied to join the navy but got so sick of waiting he enlisted in the D.L.I. and just days after joining his regiment he received word from the navy that he had been accepted. Too late, he was then a squaddie!. This was more heart ache for my Mother who had yet not quite recovered from the shock of Gavin's captivity, but as this was war she had to accept the inevitable. He eventually saw action on 'D' Day with the landings in Normandy. He was wounded on a couple of occasions during the following year of fighting and on the beach at Normandy one of his best friends was severely wounded and died from his wounds after returning home.

Gerald the third in line to go to war joined the D.L.I. IN 1942. He also saw plenty of fighting with the offensive in Italy, Egypt and Africa and was also slightly wounded in the skirmishes.Thankfully, as with the other two brothers, he survived the war and all had many stories to relate after their experiences.

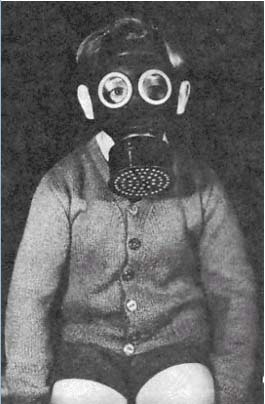

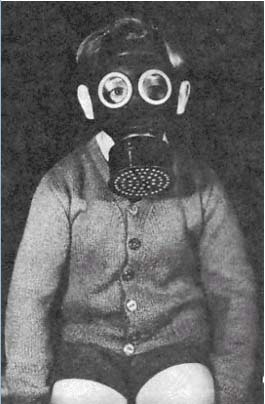

My Mother worried much about her three sons fighting for their country but it didn't end there. Life went on at home with all its problems and anxieties. Gas masks became a part of everyday life and you never felt dressed unless the little cardboard box was dangling at your side.It was the one item however, that my Mother would never let us forget! Just as we were leaving home for school the gas mask was placed over the head with the string resting on your left shoulder and the box dangling on your right side.You soon got used to carrying it and eventually hardly noticed it; just as with modern day seat belts after a while it becomes automatic. I remember vividly trying the gas mask on for the first time;the peculiar smell which rubber has albeit not an unpleasant odour; the tight feeling of the rubber around your forehead down your cheeks and under your chin, and the funny bit with everyone talking as if they had a peg on their noses. At school we were given many mock air raids (as if we didn't have enough!) to test out the gas mask. This too was very memorable because we were herded into the brick air raid shelter,built in the play yard; completely devoid of any lighting and made to run around the long wooden form running along the middle of the shelter and at the same time being urged to sing some song by one of our teachers who was somewhere in the shelter with us;add the gas masks and apart from the sight it must have been an hellish din.

I was a big boy and had a normal gas mask but my little brother Bob started his experience of the gas mask with a contraption which looked like a present-day carrycot where in case of emergency would be placed inside until the air raid was over. Not long afterwards though he progressed to a Micky-Mouse mask which we all loved to poke fun at and play around with the little,flat,rubbery piece which he had for a nose.

In the early years of the war changes were taking place so fast you could hardly keep track of them. Each day there was always something new that met your eyes. One of the first things was that the chocolate machines were not being replenished; those beautifully wrapped bars of Cadbury's,Fry's and Rowntree's were no longer available for your few coppers. Strangely they were never removed from the walls and most remained throughout the duration of the war, rusting memories of more plentiful days.And to aggravate the situation we couldn't just pop into the sweet shop and buy them, not without your sweet coupons, and just a quarter of sweets would make a nasty dent in your allocation! We couldn't even substitute our lost sweet ration for fruit because that was also in short supply,once the British crops were devoured ( which was very quickly) the fruit shops were nearly empty. Bananas became a thing of the past with too many merchant vessels being attacked and sunk before they reached the shores. Even when we heard of bananas being available it was usually an under-the-counter transaction; if you were not a regular customer they were not forthcoming. However, we school kids were sometimes in luck at Crawfords on North Road who, rather than waste apples and pears, used to cut away the bruised part of their fruit and sell the bits and pieces that were left to we kids for a penny a bag. That was usually during our dinner break and rested on whether we had a penny or not, but more often than not we could manage a penny between two or three of us!

Our problem as children, was wondering where the next ration of sweets or fruit was coming from, it was only minuscule in comparison to our Mothers' worries in feeding the

family. Belts had to be tightened as short supply was the order of the day for almost all foodstuffs. Most commodities were on the ration, all the basics required for a reasonably balanced diet were there but in meagre quantities; meat, butter, cheese, tea, sugar, eggs and many more. Even the bread we bought was off-white and speckled which said a lot about the flour! We later had the luxuries of tins of dried egg and tins of spam. The latter became a well worn musical-hall joke but at the time many of us were very thankful for it as for the dried eggs, if you had preferences for the white or the yoke then your luck was out-it was only good for omelettes! But it went down very well in my family and most others; you couldn't afford to be too finicky about your meals during the war.

But all was not glum! Not for we children anyway because there was plenty of interest in our daily existence. War had its excitement and wonders which we hadn't encountered before; plenty of events and entertainment for which we had not to travel very far to enjoy. The Army came to Sherburn Road in small units and billeted themselves not a hundred yards from where we lived; with all their weapons, tents and tanks; first in a field in Benthouse lane and again in an unused area at the rear of the George & Dragon pub. In swarms we invaded the camps gazing wide-eyed at the anti-tank guns, rifles and ammunition. We were usually welcomed by the soldiers but not allowed too close but were often very jealous of the girls who always seemed to have more privileges than we young ruffians had! These units never stayed for too long but for the short time they were there we enjoyed it tremendously.

We also, of course, had the the wonder and enjoyment of the barrage balloons. We watched them inflated and rise slowly into the sky like the smoke from the chimneys on a still summers day. There they drifted as if hanging from invisible threads.They always appeared to me like spacecraft from Flash Gordon serials heading for space to attack and destroy Ming and the Clay People. I suppose they must have served their purpose during the war but we in Durham never saw any example of it.

We weren't without our moments in Durham, however. Stray bombs did drop around the town and the nearest one fell at Shincliffe. When awake during air raids we could hear distant explosions, no doubt around the Sunderland area and other ports who were less lucky than ourselves.But we did have a peculiar advantage in Durham City; although we were submerged in all the war time trappings we never witnessed any bombardment of life threatening dimensions as did the coastal regions from Hartlepool to Tyneside and even further up the Northumbrian coast. The shipping and coal industries were prime targets for the German bombers and I remember vividly the destruction caused in Sunderland when visiting that town just after the war; the scars were still prominently visible from those strife torn six years.

The war effort strangely changed part of the physical landscape of the City.Suddenly all around the town iron railings were being ripped from house and building perimeters. You couldn't help but feel sorry for house owners, who overnight,witnessed the removal of the secure and cosmetic properties of the railings which in most cases added charm and quality to their homes.Even the old, locally built canons, on the battlements at Wharton Park were removed and used for the war effort;but I believe one was spared which later stood outside The Dunelm Club in Elvet.

Even as children we at St Godric's School contributed our share to the war effort although in one instant it had its ups and downs. All the children in the city in their own various ways collected waste paper and I remember Skipper Chalmers, that noted scout leader of the 5th Durhams, scouring the town with his troops massed on his old car and loaded with whatever was needed. I believe that he was one of the most admired adults in the town in the eyes of most children and his name will always be synonymous with the local scout movement. Our own school effort involved most of the boys assembling in small groups of about four at dinner times and visiting the shops in the vicinity of the North Road and collection sacks of waste paper and cardboard boxes. Once we had filled our sacks we returned to the school and deposited the contents into one of the cloak rooms adjacent to the senior boys playground. Naturally the cloak rooms were heaped with waste paper ready for collection by the council. On one particular afternoon we boys in my group decided to have a bit fun jumping into the mounds of waste and scattering the contents to all corners of the cloakroom, consequently it was like a disaster area. Unfortunately for us though our Head Mistress, Sister Mary Gabrielle, caught us in the midst of our excitement. She was a wonderful woman, well liked by all the pupils but that didn't stop her from chastising us with two smart whacks of the cane:one on each hand.The collecting of waste paper was a strictly serious activity after that episode!

Another major development at the start of the war involved the digging of trenches and we at St Godric's were lucky to have a network of them just outside our main gate on the embankment between Framwellgate and the Railway Station. Soon after the commencement of the war,gangs of men were frantically digging a maze of connected trenches about three or four feet deep. At first the trenches were of grave importance for the war effort and we children from the school were strongly discouraged from playing anywhere near them; after all the strategy was, I believe, to physically withstand the enemy if we ever had the misfortune to have to combat the enemy on our own soil, as, of course, most of Europe had to do. But as the threat subsided so the trenches became obsolete and we took over as an extension to the playyard. However, like all children, our interest soon waned and nature reclaimed the trenches which became waterlogged and overgrown.

On another occasion,while heading for school through the Market Place we discovered a captured German aeroplane standing just outside the Town Hall. Where or when it had been captured we never knew but it generated plenty of excitement with scores of children and adults milling around the plane in an effort to have a closer look. One or two of the kids managed to sit in the cockpit but I wasn't so lucky. We did find out later that it was a German Messershmit fighter aircraft and I often wondered what had happened to the pilot? He may even have been on the mission to bomb the Cathedral and Silver Street as Lord Haw-Haw had threatened to do over the radio in one of his notorious propaganda speeches. His was always one of the names bandied about by the adults in venomous tones when ever one of his broadcasts had been heard. Other infamous Nazis which we soon learned to despise as everyone else did were; Hitler,ofcourse, and Goering, Ribbentrop, Goebbels, Hess,and the Italian Dictator, Mussolini. These were just a few which were forever assailing our ears,especially in the newsreels at the pictures and they were also the butt of our famous comedians such as Tommy Handly,Arthur Askey, and George Formby for example. There was a well known propaganda piece in George Formby's film "Let George Do It" where he had a dream and was drifting over Germany in a balloon and over a gathering where Hitler was making one of his fiery speeches; Formby let himself down to the platform where Adolf and his henchmen were gathered and started to fight and remonstrate with Hitler with great cheers from the audience but it was at this point that he woke up. In later years I learned that the film makers were quite adept at producing these propaganda films which at the time very few of us were aware, but it worked wonders with our morale.

One of the greatest morale boosters of the war was music. whether it was just the strains of 'Music While You Work' with such classics as 'Jealousy'or'A Nightingale Sang In Berkeley Square',or listening to the variety of good vocalists on 'Housewives Choice' and 'Family Favourites', it all contributed to bolstering the spirits of our overworked nation. On another radio program,'Workers Playtime,' whether it was from a works canteen, factory or a service base, every one joined in the vocal refrains of such favourites as;

"We'll Meet Again,' ' The White Cliffs Of Dover'(Two Vera Lynn classics) 'Somewhere In France With You' (Chuck Henderson) and scores more. I didn't need the sheet music to learn the words of all these songs because my Mother was forever singing them; the songs were a great relief for the tension and stress which accompanied her throughout the war years. 'When The Lights Go On Again,' she sang from the heart as also she did with;'Somewhere In France With You'. The feeling was always there and no doubt her thoughts were forever with her three sons away on foreign shores,longing for the time when she would see them walk through her doorway once more, when the lights would go on again, 'All over the world!'

Nearly everyone appeared to be wearing a uniform in those far off bleak days. Not only men but women as well. Obviously we had the three main services of the Army, Navy and Air Force but there were many others donning uniform mostly involved as local protection units propagated by the advent of the war and all part of our Civil Defence. The Auxiliary Fire service added strength to the regular brigade especially with the loss of some of the younger men who managed to enlist into the forces; but also we had the Observer Corps, The Home Guard and the Air Raid Wardens (A.R.P.) to name but a few who were all milling around the town and all doing their bit! They all became part of our existence for over five years but luckily they were never called upon to face the death and destruction that other cities and towns had to endure.

Besides the local uniformed units, thousands of other workers were carrying out duties under very hazardous conditions. Both Birtley and Ayecliffe were producing war materials in their factories; every day handling highly dangerous and explosive commodities and involving both men and women in very volatile conditions. Danger was a constant companion with the workers and many paid the ultimate price for their efforts. It is only lately that they have received the recognition that they deserved, they were always the unsung heroes and heroins of the last war. My Father was employed doing this work at Birtley until his death in 1944 and my Mother, Shortly after my Father's death, worked at Ayecliffe for the remainder of the war. Shift work was the norm, regardless of what family you might have at home. Luckily my sixteen year old sister took over the 'Mother' figure in the home while my Mother was engaged in this important occupation of war production.

Towards the latter years of the war we began to see the strange phenomenon of German and Italian prisoners of war working in our area. Most of these worked on local farms in small groups with the farmer and also Land Army girls who were also among the unsung heroins of the war.The strange thing was that we never seemed to see any guards with the prisoners; probably they were on complete trust or the guard was camouflaged as a tree! At no time were we ever witness to these prisoners running away or causing any sort of problem for the authorities. Infact the Italian prisoners used to walk around Durham in small groups as if they were just 'window shopping'; they also never appeared to have an escort. The one unsavoury aspect with the Italians walking about was that if any group of our own soldiers were in the vicinity we sometimes witnessed aggression and abuse from our own men; possibly they had been involved in fighting in Italy and saw some of their own comrades wounded or even killed, which provoked them into this aggressive behaviour on seeing the Italians walking freely around the town. But thankfully these little episodes were few and far between.

About 1942 Dryburn was opened as a Military Hospital and we were always able to tell when our lads were patients at the hospital because they all wore distinctive blue uniforms. As the war progressed the numbers seen walking around the town increased as hundreds of our men were admitted for treatment and I don't suppose they were ever too keen to return to the fighting once their wounds were healed.

One outstanding memory I shall never forget was the announcement of the end of the war. I didn't hear it from the radio or from family or friends. I was in my second year at St Leonard's School and a pupil of Miss Burns. We had just finished our dinner break and my class was streaming into the classroom; as we were heading for our desks, Miss Burns was busy chalking a sentence on the board, and as we all sat down she called for our attention, and with her finger pointing at each word, slowly and with pride, she read the sentence from the black board for all to hear," Victory In Europe,May 4th 1945." There was a terrific roar and cheer from the classroom and the whole school seemed to erupt. On returning home that evening I had half expected our Gavin to be home after being a prisoner for so long but it was only childish, wishful thinking.

His story of that momentous time in history was far less glossy than our own spontaneous celebrations of victory over the Germans. He later related that,when the Germans realised that the end of the war was near, he and thousands of other prisoners were marched from Poland to Hanover, a distance of over five hundred miles.. Many died on the journey and many more became gravely ill with illnesses such as dysentery because of the lack of food and the proper sanitary conditions. The weather was extremely cold and their boots and clothing were very inadequate;boots were wearing out but there were no replacements,also, most of their clothing was scanty and very inappropriate for the severe conditions of the march. The survivors eventually reached Hanover where many (Gavin included) were admitted to hospitals which lacked much of the basic medicines and treatment. However their deliverance was near when the Americans arrived and took over the hospitals and the treatment of the prisoners. Gavin was eventually transported to England by an American hospital 'plane and within a short while was heading towards home. His return was one of the events of our lives and will always be remembered by family and friends. The bunting was strung across the street and pennants draped from various windows of the street with the words,"Welcome home Gavin". He arrived at Durham Station and was met by Ralph and Peg, my brother and sister. He had expected to see my Father waiting but because of the circumstances he was never informed of his death. His first words asked why wasn't his Father there to meet him; but he understood very quickly when Peg burst into tears. My Mother was shedding more tears as she waited patiently at home with the rest of us which included myself and my three other brothers; John, George, and the youngster,Bob; the only two missing were Peter and Gerald who were still abroad: one in Germany and the other in Italy. Our home was bulging with relations and friends and most of the street was waiting to give Gavin a welcome as he arrived in a taxi. He later said that he had wished it could have been quieter with less people to greet him but he fully appreciated their kindness with the reception he received from them. The unforgettable moment was my Mother greeting this tall, gaunt stranger that I watched walk through the door. For all the commotion and noise of the greeting the only two that mattered for many moments were my Mother and her long lost son embracing in the middle of the floor and crying away the bitter years of Gavin's captivity. What A wonderful memory!

Postscript.

The remainder of the war with Japan was only an anti-climax. People began to return to normal but very slowly as rationing was to remain for a few years yet. My Mother's other two sons, Peter and Gerald eventually were discharged but without the pomp

that Gavin had received after being a prisoner for over five years.They had served their country over the long years of fighting the enemy as millions more had done,but thank God they returned from the carnage alive! I suppose with three sons engaged in the war, in a perverted sense, My Mother was lucky that they all returned home safely.

Phil Clark

|